What is Acute otitis media? What are causes,risk Factors, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and prevention

Acute otitis media

Acute otitis media is a bacterial or viral infection of the middle ear, usually accompanying an upper respiratory infection. Symptoms include otalgia (ear pain), often with systemic symptoms (eg, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), especially in the very young children. Diagnosis is based on otoscopy. Treatment is with analgesics and sometimes antibiotics.

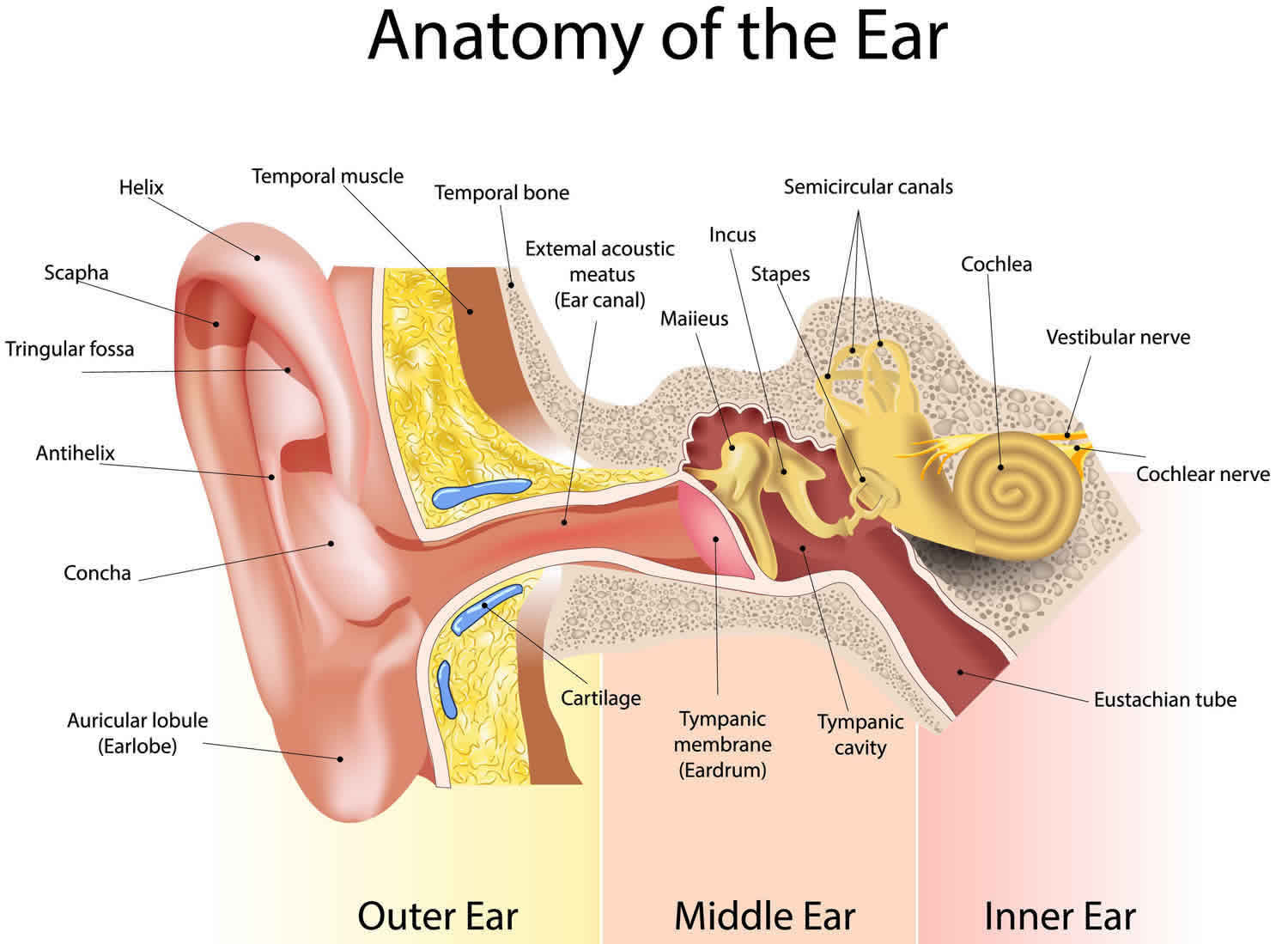

Although acute otitis media can occur at any age, it is most common between ages 3 months and 3 years. At this age, the eustachian tube is structurally and functionally immature—the angle of the eustachian tube is more horizontal, and the angle of the tensor veli palatini muscle and the cartilaginous eustachian tube renders the opening mechanism less efficient. Anything that causes the eustachian tubes to become swollen or blocked makes more fluid build up in the middle ear behind the eardrum.

The cause of acute otitis media may be viral or bacterial. Viral infections are often complicated by secondary bacterial infection. In neonates, Gram-negative enteric bacilli, particularly Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus cause acute otitis media. In older infants and children < 14 years, the most common organisms are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis, and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae; less common causes are group A β-hemolytic streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus. In patients > 14 years, Streptococcus pneumoniae, group A β-hemolytic streptococci, and Staphylococcus aureus are most common, followed by Haemophilus influenzae.

Acute otitis media causes

Acute otitis media usually starts with a cold or a sore throat caused by bacteria or a virus. The infection spreads through the back of the throat to the middle ear, to which it is connected by the eustachian tube (also called auditory tube). The infection in the middle ear causes swelling and fluid build-up, which puts pressure on the eardrum.

Acute otitis media are common in infants and children because the eustachian tubes are easily clogged. Acute otitis media can also occur in adults, although they are less common than in children.

The eustachian tube runs from the middle of each ear to the back of the throat (see Figures 1 and 2). Normally, the eustachian tube drains fluid that is made in the middle ear. If the eustachian tube gets blocked, fluid can build up. This can lead to infection.

Anything that causes the eustachian tubes to become swollen or blocked makes more fluid build up in the middle ear behind the eardrum. Some causes are:

- Allergies

- Colds and sinus infections

- Excess mucus and saliva produced during teething

- Infected or overgrown adenoids (lymph tissue in the upper part of the throat)

- Tobacco smoke

Acute otitis media are also more likely in children who spend a lot of time drinking from a sippy cup or bottle while lying on their back. Getting water in the ears will not cause an acute ear infection, unless the eardrum has a hole in it.

Usually, acute otitis media is a complication of eustachian tube dysfunction that occurred during an acute viral upper respiratory tract infection. Bacteria can be isolated from middle ear fluid cultures in 50% to 90% of cases of acute otitis media and serous otitis media 1). Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae (nontypable), and Moraxella catarrhalis are the most common organisms 2). Haemophilus influenzae has become the most prevalent organism among children with severe or refractory acute otitis media following the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

Acute otitis media most often occur in the winter. You cannot catch an ear infection from someone else. But a cold that spreads among children may cause some of them to get ear infections.

Adults

There is little published information to guide the management of otitis media in adults. Adults with new-onset unilateral, recurrent acute otitis media (greater than two episodes per year) or persistent otitis media with effusion (greater than six weeks) should receive additional evaluation to rule out a serious underlying condition, such as mechanical obstruction, which in rare cases is caused by nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Isolated acute otitis media or transient otitis media with effusion may be caused by eustachian tube dysfunction from a viral upper respiratory tract infection; however, adults with recurrent acute otitis media or persistent otitis media with effusion should be referred to an otolaryngologist.

Risk factors for acute otitis media

The presence of smoking in the household is a significant risk factor for acute otitis media. Other risk factors include a strong family history of otitis media, bottle feeding (ie, instead of breastfeeding), and attending a day care center.

Risk factors for acute otitis media 4):

- Age (younger)

- Allergies

- Craniofacial abnormalities

- Exposure to environmental smoke or other respiratory irritants

- Attending day care (especially centers with more than 6 children)

- Family history of recurrent acute otitis media

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Immunodeficiency

- No breastfeeding

- Pacifier use

- Upper respiratory tract infections (URTI)

- Changes in altitude or climate

- Cold climate

- Not being breastfed

- Recent ear infection

- Recent illness of any type (because illness lowers the body’s resistance to infection)

Acute otitis media prevention

Routine childhood vaccination against pneumococci (with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine), Haemophilus influenzae type B, and influenza decreases the incidence of acute otitis media. Infants should not sleep with a bottle, and elimination of household smoking may decrease incidence. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for children who have recurrent episodes of acute otitis media.

Recurrent acute otitis media and recurrent secretory otitis media may be prevented by the insertion of tympanostomy tubes.

Good information keep it👍

ReplyDelete